This is not intended to be a complete guide to moth trapping, so we would be very happy if you could share your own knowledge and experience.

- Guides

- Influence of moth trap design and light source on moth capture rates

- Classical Moth Trapping

Guides

Influence of moth trap design and light source on moth capture rates

- Entomological lamp comparison

- Short- vs. long-wavelength light in moth attraction

- UV-LEDs outperform actinics for standalone moth monitoring

- Assessing the efficiency of UV LEDs as light sources for sampling the diversity of macro-moths (Lepidoptera)

- Effect of spectral composition of artificial light on the attraction of moths

- Effect of bulb type on moth trap catch and composition in UK gardens

- Assessing the value of the Garden Moth Scheme citizen science dataset: how does light trap type affect catch?

Classical Moth Trapping

Classical moth traps are among the most widely used and historically important tools in nocturnal Lepidoptera research. Long before the development of automated video tracking, harmonic radar, or telemetry-based approaches, these traps enabled entomologists to systematically sample moth communities and build the long-term datasets that still underpin our understanding of moth diversity, phenology, and population change.

This page provides an overview of the most common classical moth trap designs, their operating principles, strengths, and limitations, with a focus on their relevance for modern ecological and behavioural research.

General principle

All classical moth traps exploit the strong attraction of many nocturnal moths to artificial light, particularly light rich in ultraviolet (UV) and blue wavelengths. A light source draws moths from the surrounding area, while the trap structure (funnels, baffles, or enclosed boxes) guides them into a collecting chamber.

Importantly, these traps are passive sampling devices. They do not actively pursue insects or impose directional cues, but rely on natural phototactic behaviour. As a result, they are especially valuable for standardized monitoring and comparative studies across sites and years.

Main classical trap designs

Robinson trap

The Robinson trap is often regarded as the reference design for quantitative moth monitoring. It consists of a large box with a wide funnel beneath a powerful light source, traditionally a mercury vapour lamp.

Characteristics

- Very high catch efficiency

- Captures a broad taxonomic range of species

- Bulky and relatively heavy

- High power consumption

Typical applications

- National and regional monitoring schemes

- Long-term population trend analyses

- Species-rich habitats where maximum catch efficiency is required

Skinner trap

The Skinner trap is a more compact, box-shaped design using vertical baffles to deflect moths downward into the collecting chamber.

Characteristics

- Portable and easy to deploy

- Compatible with mercury vapour and actinic light sources

- Slightly lower catch rates than Robinson traps

Typical applications

- Multi-site surveys

- Standardised monitoring across landscapes

- Private and academic recording programmes

Heath trap

The Heath trap is a lightweight design commonly used with low-power actinic tubes. It is especially popular where portability and low energy consumption are priorities.

Characteristics

- Low power requirements

- Can be battery operated

- Selective towards UV-sensitive species

Typical applications

- Remote or power-limited field sites

- Garden and small-scale monitoring

- Comparative studies using standardized low-intensity light

Rigid moth trap (bucket or rigid-box trap)

Rigid moth traps are a simplified and durable variant of classical box traps. They are typically constructed from rigid plastic containers (such as buckets or purpose-built plastic boxes) fitted with internal vanes and a small light source. Because of their robustness and simplicity, they are widely used in standardized monitoring schemes and volunteer-based recording networks.

Characteristics

- Mechanically robust and weather-resistant

- Compact and easy to transport

- Usually operated with low-power actinic or LED UV light sources

- Lower catch efficiency than Robinson or Skinner traps

Typical applications

- Long-term monitoring programmes

- Citizen-science and volunteer networks

- Repeated sampling at fixed sites

Light sources in classical traps

Mercury vapour lamps

Mercury vapour lamps were historically the dominant light source in classical moth trapping. They emit intense UV and visible light and attract a wide diversity of moth species.

Advantages

- Very strong attraction

- High species richness

Disadvantages

- High heat output

- Fragile bulbs

- Increasing regulatory restrictions

Actinic fluorescent tubes

Actinic tubes emit cooler, narrower-spectrum UV-rich light and have become a common alternative.

Advantages

- Lower heat and power consumption

- Safer and easier to standardise

- Suitable for long-term comparative monitoring

Disadvantages

- Lower overall catch size compared to mercury vapour

UV LED light sources

UV light-emitting diodes (UV LEDs) represent a more recent development in moth trapping and are increasingly used in rigid traps, portable light traps, and automated monitoring devices. They typically emit light in narrow wavelength bands (commonly 365–405 nm), targeting the spectral sensitivity of many nocturnal moths.

Advantages

- Very low power consumption

- Minimal heat production

- Long lifespan and mechanical robustness

- Easily powered by batteries or solar systems

- High reproducibility between units

Disadvantages

- Narrow spectral output compared to mercury vapour or actinic lamps

- Often attract fewer species overall

- Species composition may differ substantially from traditional light sources

Low-cost and DIY alternatives

In recent years, a wide range of low-cost and do-it-yourself (DIY) moth traps have emerged, driven by advances in LEDs, microcontrollers, sensors, and affordable fabrication methods. DIY light traps typically combine a simple enclosure (plastic box, bucket, or funnel), a low-power UV LED or actinic light source, and basic internal vanes or baffles. Many designs can be assembled from readily available materials at minimal cost.

Dutch Butterfly Conservation design

UKCEH design

Blogpost and Biological Recording Company webinar

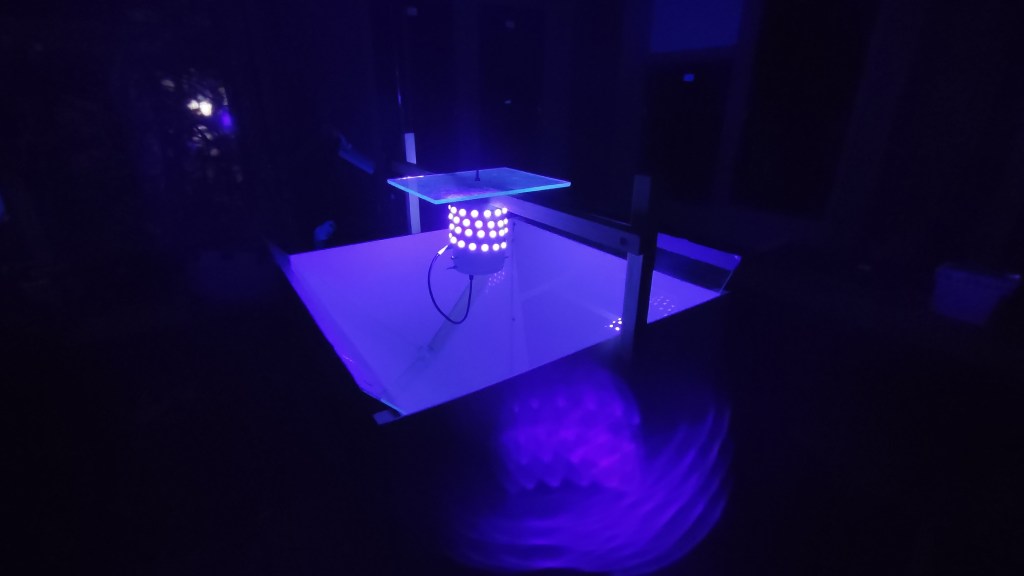

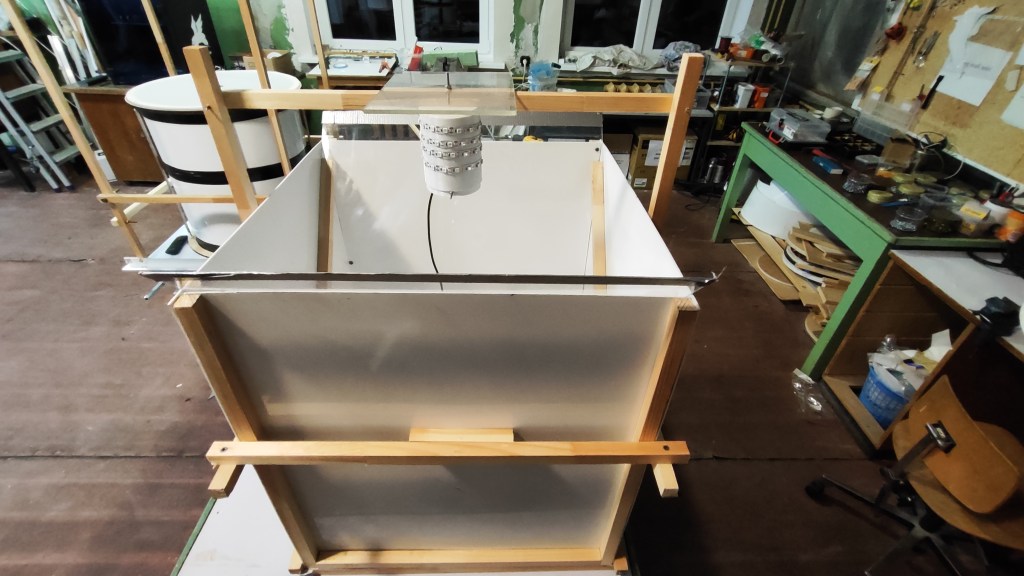

Our design

More info here

Other classical methods

Sugar (bait) traps

Sugar traps, also known as bait traps, rely on olfactory rather than visual attraction. A fermenting mixture—traditionally based on sugar, molasses, beer, wine, or fruit—is applied to tree trunks, posts, or suspended ropes shortly before dusk. Nocturnal moths are attracted to the volatile compounds released during fermentation and settle to feed on the bait.

Recipe:

- our recipe which was successfully used to catch Red Underwings (Catocala nupta) and Clifden Nonpareil (Catocala fraxini) in Austria (Autumn 2025): mixture of 500 ml red wine, 500 g sugar, honey, cherry jam and 50 ml bitters

Characteristics

- Do not rely on artificial light

- Particularly effective for species weakly attracted to light

- Allow direct observation and selective sampling

Typical applications

- Sampling autumn-flying and late-season species

- Surveys in light-sensitive or protected habitats

- Complementary sampling alongside light traps

Limitations

- Strong bias towards nectar- and sap-feeding species

- Highly dependent on bait recipe, temperature, and humidity

- Poor standardisation across studies

Cotton sheet and UV lamp traps (light sheets)

Light-sheet trapping combines a vertical cotton sheet (or white fabric) with an ultraviolet or mercury vapour lamp positioned in front of it. Moths attracted to the light settle on the illuminated surface, where they can be observed, photographed, identified, or temporarily collected.

We recommend using a LepiLED UV lamp, which is powered by a power bank and is effective at attracting a wide range of species (in Europe). US analog – Entoquip UV light or EntoCam beam

Additionally, it can be used in combination with a powerful searchlight (e.g. a 1000 W halogen lamp or a high-output LED) to attract high-flying migratory moths (Underwings in Europe and Bogong moths in Australia).

Characteristics

- Highly interactive and non-destructive sampling method

- Enables real-time observation of behaviour and activity patterns

- Flexible setup adaptable to many habitats

Typical applications

- Rapid biodiversity assessments

- Behavioural observations at light

- Photographic documentation and voucher selection

Limitations

- Strongly observer-dependent

- No enclosed collecting chamber (individuals may leave at any time)

- Less suitable for quantitative abundance estimates